The Frankenstein Constituency: Why Gorton and Denton Looks Like This

By now, many people have seen the potential Gorton and Denton voting map based on census data, created by Josh Housden and shared on X.

This spurred a lot of debate around constituencies makeup, the Boundary Commission, and the very essence of what makes up a constituency. As Luke Tryl noted, this looks like two different constituencies wanting two different thing from an MP.

How did Gorton and Denton come to be?

Gorton and Denton was stitched together from the remnants of two abolished seats - Manchester Gorton and Denton and Reddish - with Burnage ward from Manchester Withington thrown in for good measure. It has the fourth-highest index of change in the North West, meaning its electorate has been reshuffled more dramatically than almost any comparable seat.

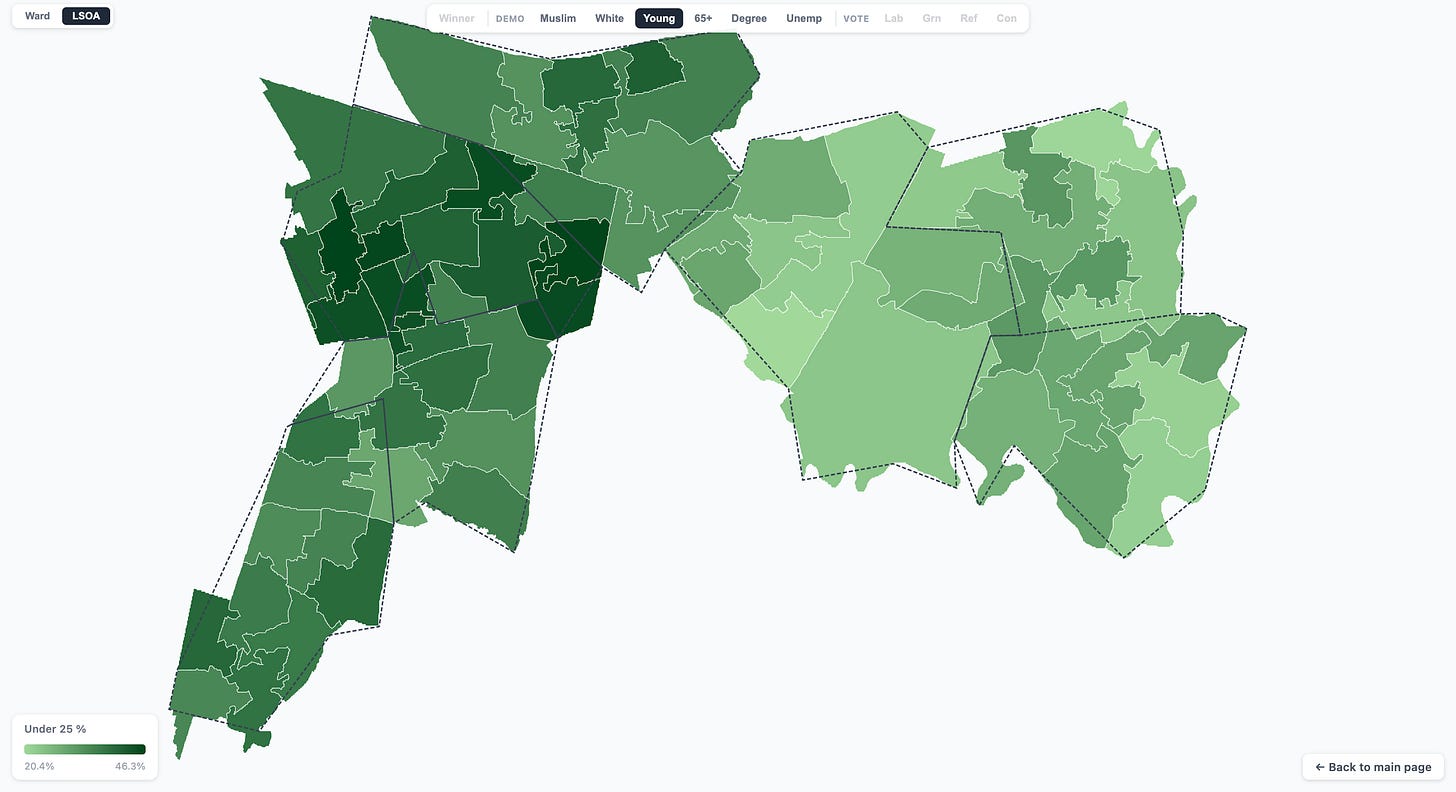

Much of the demographic challenges were covered in my previous article , but to recap, the Manchester wards are 42% white and 40% Muslim, with 42% of residents holding or studying for a degree. The Tameside wards are 83% white, 86% UK-born, and heavily working class. It spans two local authorities, and two competing electorates.

The PollCheck interactive constituency map for Gorton and Denton can be used to see the spread of demographics in a heat map

Who decides what makes a constituency?

Constituency boundaries are drawn by The Boundary Commission for England, an independent, non-partisan body chaired by a High Court judge. It cannot consider voting patterns and is explicitly forbidden from thinking about electoral outcomes. It operates under rules set by the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, most recently amended in 2020.

The Commission’s main priority is the 5% rule - every constituency must have an electorate within 5% of the UK-wide electoral quota. For the 2023 review, that quota was 73,393 voters, giving a permitted range of 69,724 to 77,062. Only five island seats are exempt.

Only after meeting this 5% rule can the Commission consider softer "Rule 5" criteria: existing boundaries, local government boundaries, local ties, and geography. The Commission uses council wards as building blocks, and prefers not to split them, as wards are considered "well-defined and well-understood units" indicative of community interest.

The issue comes in when meeting this quota doesn’t fall neatly within existing boundaries. The abolished Manchester Gorton was too large to survive intact. The Denton wards couldn’t form a viable constituency within Tameside alone. In the end, Denton had to be paired with inner-city Manchester wards, and Burnage was added to bring the numbers into range.

The Commission has been explicit that it would prefer a 4% variance constituency that respected local ties to a 1% variance one that split communities. But it cannot prefer any configuration outside the 5% window, no matter how much local sense it makes.

What should a constituency be?

The question becomes, what do we want from a constituency? A core principle of FPTP, especially in the UK, is that an MP represents a local area. Ostensibly, we vote for a local MP, not a party. Ideally, an area would have enough in common that a single MP can adequately represent their interests in Westminster, as well as work on constituency matters locally.

Does this happen in Gorton and Denton? Labour, Reform and the Greens are all targeting the working class vote. However, where Reform might concentrate on the ‘left behind’ white working class, the Greens may also concentrate on Gaza and wealth tax. Labour will want to be appealing to both sides.

A constituency like this could start to strain FPTP:

Thin mandates. Labour won 50.8% in 2024, but behind them, opposition fragmented: Reform at 14.8% (concentrated in Denton), Greens at 13.2% (Manchester wards), Workers Party at 10.3% . It’s certainly possibly the winner of the by-election could win with under 30% of the vote.

Perverse campaign incentives. As I wrote previously, Reform could concentrate on turning out the whiter and older areas of Denton, relying extremely heavily on the older population who have higher vote propensity. The Greens could concentrate on firing up Levenshulme, Longsight and Burnage. A message a party uses in one area may not work in the other - giving incentive to run two parallel but different campaigns.

Broken tactical voting. Who the “main challenger” is depends on where you live. Anti-Labour sentiment in Denton points to Reform; in Levenshulme it points to the Greens. There’s no single tactical vote, so the anti-incumbent vote splits, again leading to parties winning on ever smaller shares.

What might actually help?One reform that’s been suggested is loosening the 5% quota.

Before 2011, the Commission had broader discretion to deviate from the quota. The Constitution Unit at UCL has argued the strict 5% rule forces numerical equality above all else, producing more Frankenstein constituencies than necessary.

In opposition, Labour proposed change to The Parliamentary Constituencies Bill 2019-21 that would have increased the tolerance to 7.5%, which would have lessened the impact of changes on communities.Another larger question is whether FPTP itself is the problem. Wales is about to test a different approach: the Senedd's 2026 election will use a fully proportional closed-list system with 16 six-member constituencies, created by simply pairing up existing Westminster seats.

Under this model, a seat like Gorton and Denton could elect multiple representatives from different parties that could serve the same area, and a community making up 28% of the constituency could realistically elect at least one of six members.For now, voters go to the polls on 26 February to choose a single MP for a seat containing potentially different political worlds. The Boundary Commission followed its rules. The maths worked out. The constituency exists. How well it works remains to be seen.